Change of Address

This month has been… well, chaotic. I didn’t anticipate just how complicated moving would be but I feel hopeful and excited about the changes. I’ve been thinking about what this move means and how it compares to the ways families lived in the past. Anchoring my own experiences in those of my grandparents, examining the differences and similarities, has helped me reimagine this process and contextualize this chaos.

Like many Millennials, we are taking our turn living with my parents. Our rent was raised almost 30% and although we understood we’d gotten a “pandemic deal” on our apartment two years ago, the arbitrariness and unpredictability of the rent hike shook us. I started having trouble envisioning a life in NYC that would allow for any kind of stability for our son. Already, the idea of moving him from his current daycare makes me feel sick to my stomach. We found a solution – what feels like a lucky break in a fickle town – and are now in the midst of moving just a mile away, to Harlem.

Our stay with my parents is temporary – only due to a mismatch between move-out and move-in dates -and luckily doesn’t require relocating to another city. But the challenges of moving with a toddler have encouraged me to think about this phenomenon facing so many people my age in a broader perspective. For one, I can’t stop thinking about how lucky we are to have this option. The cost of moving is high, with constant unforeseen expenses. Add temporary housing or a lack of familial support to that mix and I don’t know how anyone does it.

I’m not alone in having a young family (with two full-time incomes) relying on help from their Baby Boomer parents to forge a comfortable life. People have been quick to blame Millennials for difficult financial circumstances – with a famous focus on buying avocado toast (which I have never done!) – rather than exorbitant corporate tax breaks and price gouging, a housing bubble that burst the year I graduated from college, depletion of social services and safety nets, a global pandemic, and now inflation – for their inability to purchase a home, save for retirement, or pay down credit, student, and medical debt.

But I’ve begun to think about this move in with my parents not as a new phenomenon but as a historical one. One that links back to the days when multi-generational housing was commonplace. The nuclear family, living in a stand-alone house on a street far from their extended families, with strict socio-economic and racial segregation, is a relatively recent and an intensely modern idea. And it’s hard, it’s cruel, and it is often unsustainable.

Certainly, I don’t want to romanticize the poverty, bigotry, and constraints immigrant families like my own faced in coming to New York/America and squeezing into small spaces. Nor do I want to ignore the fact that sleeping on a pull-out couch in the living room prohibits my dad from watching baseball games, or that my mom works at her desk next to a diaper pail full of my son’s refuse. Still, despite the inconveniences, I can’t help but feel excited and moved by the fact that giving up privacy also means we are less alone in our daily toils and my son sees his grandparents every single day. Suddenly, I have an extra pair of eyes around to watch him while I get us both dressed and out of the house in the morning. Without having to coordinate (or pay!) I have just the littlest bit of freedom to brush my teeth without wondering if my son is sticking his hands in a doorjamb. I find myself with that much more presence of mind to just be with him and enjoy him.

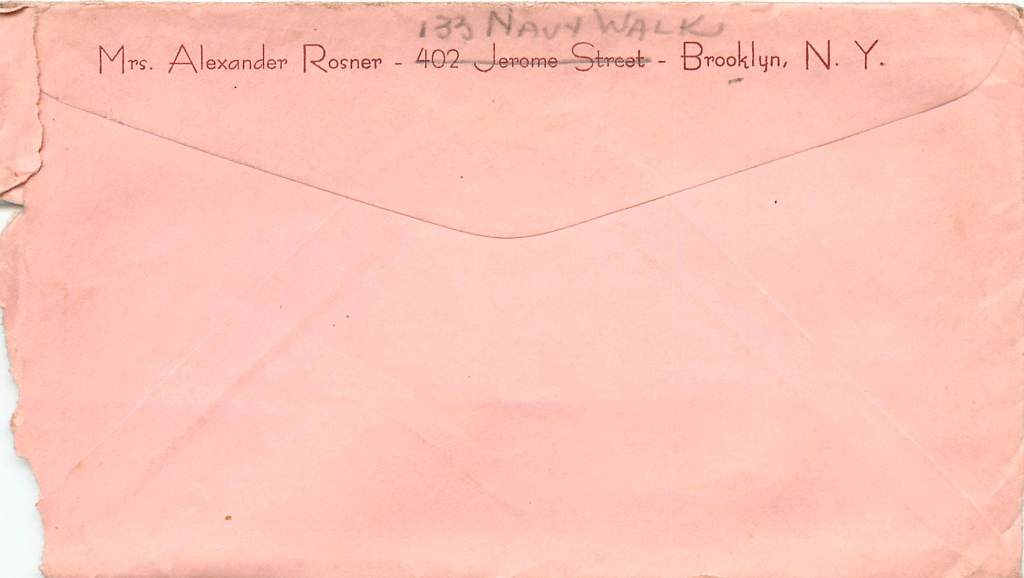

All this being said, I don’t have the bandwidth to post about an entire letter right now. So instead, I share a little clipping of a piece of paper you’ve seen before.

Much of the stationary that Silvia uses to write to Alex has her married name (or, rather, her husband’s name) but her parents’ address on it. Marriage didn’t mean immediately leaving home, though her excitement when they finally get their own space is palpable. This stationary is physical documentation of Silvia’s identity as both wife and daughter – which she navigates throughout the letters. When my grandparents moved to the Navy Yard projects during the war, she continued to use the stationary with the address crossed off.

She was disciplined about crossing it off on each and every page, though it’s clearly still legible. In this small way, she was crossing off – or making secondary – a part of her identity, but not throwing it away altogether. I don’t see anyone arguing that the “Greatest Generation” couldn’t afford their own homes because they were frivolously buying small treats for themselves (or the fact that it took a massive public housing effort as well as the GI Bill for many families to afford their own home). The expectation of post-war America – that everyone live alone with only their partner and child – simply collapses under pressure.

I feel excited about the changes we are about to make but in the meantime, I am finding that it feels different to live in my parents’ household as a mother instead of only as a daughter. While I bristle at many of the same interactions that caused me frustration as a teenager, I relish watching them indulge in grandparenthood: beaming at my son’s accomplishments, and praising his new walking skills, good nature, and growing comprehension of the world.

Also, they have a great view.

Discover more from Brooklyn in Love & at War

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.